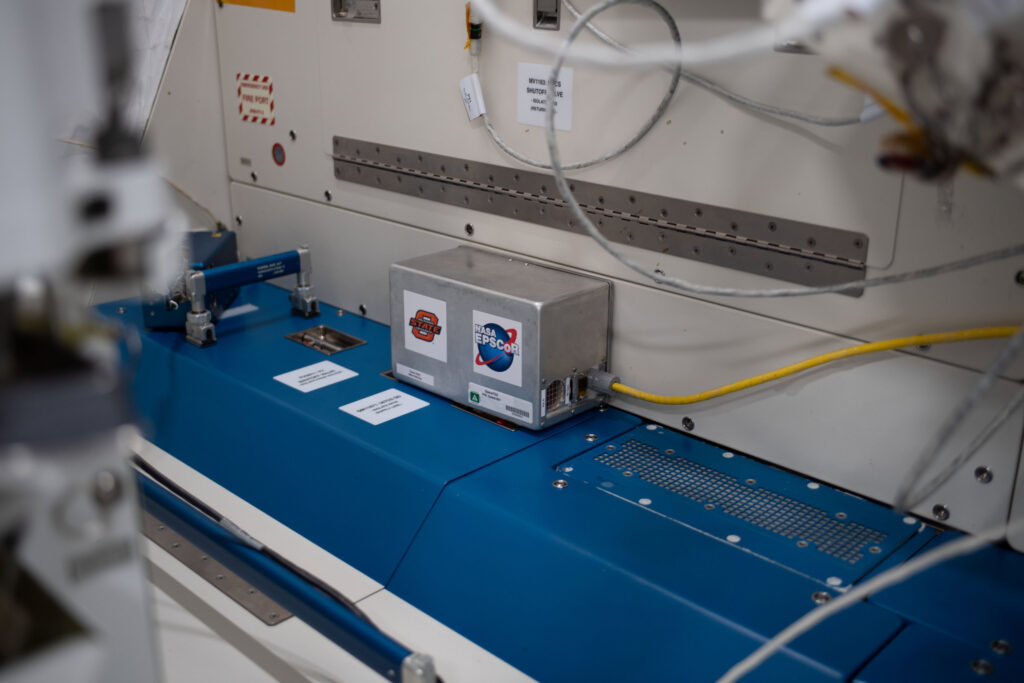

STILLWATER, Okla. (OBV) – A radiation detector engineered at Oklahoma State University was installed in the International Space Station and is being used to transmit huge batches of data back to Earth.

Dr. Eric Benton and Ph.D. student Tristen Lee built the radiation detector – called SpaceTED, short for Space Tissue Equivalent Dosimeter – and were ecstatic when they learned in November that their creation was successfully installed in the Space Station.

“This is the biggest thing I’ve done in my life so far,” said Lee, who joined OSU in 2019 to do research with Benton. “The work itself was gratifying, but to see the launch go successfully, it was like a big weight lifted off my shoulders. And then to see the first round of data come back and realize I’m going to get a Ph.D. out of this? Yeah, it was a feeling of relief and then satisfaction.”

NASA funds SpaceTED through an Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) award, according to OSU officials.

SpaceTED might be just the size of a child’s shoebox, but its contribution to the space station is enormous. It has a unique radiation detector inside it called a tissue equivalent proportional counter.

“A TEPC is a type of radiation detector designed to mimic the response of human tissue to ionizing radiation,” Lee said. “This allows for more accurate measurements of radiation doses that could be delivered to the human body than from, say, a Geiger counter.”

Lee and Benton’s research is not only making a difference in outer space but also here on Earth. Military flyers and professional flight crew members are exposed to higher levels of radiation than those on the ground, but regulating acceptable exposure is based exclusively on estimates and computer models.

“But the computer models have not been validated very well with actual measurements,” Benton said. “The work that NASA is sponsoring is largely in support of getting those measurements.”

Benton received his first NASA grant in 2007. SpaceTED evolved through multiple prototypes.

“This is actually the third radiation detector built for installation on the International Space Station. The first one was destroyed. It was on a FedEx truck that was involved in an unfortunate accident that caused the truck and its cargo to burn up,” Benton said. “The second one made it to the space station in 2018 and was supposed to last for six months but was kicked by an astronaut. They busted off the whole SD card drive, and they could hear it floating around inside the case.”

SpaceTED was installed in the Japanese Experiment Module, a less trafficked area in the Space Station.

“Fortunately, they gave us a second chance,” said Benton, who saw each setback as a chance to improve. “The first thing I did after receiving the news that the detector was kicked was write this huge list of lessons learned and all the things I’d do differently. I handed it to Tristen and said, ‘OK, build a better one.’ And he did.”

OSU researchers receive new batches of data to sift through every couple weeks. The data comes in two columns of numbers, and each row in a column represents the amount of energy deposited by ionizing radiation in the detector. The first batch had 38 hours of data – around1,700 files.

“We’ll put the data through various conversion routines, and it will give us what’s called the absorbed dose,” Lee said. “This is a quantity used to measure the amount of radiation a person receives — whether it’s from X-rays at the dentist or space travel.”

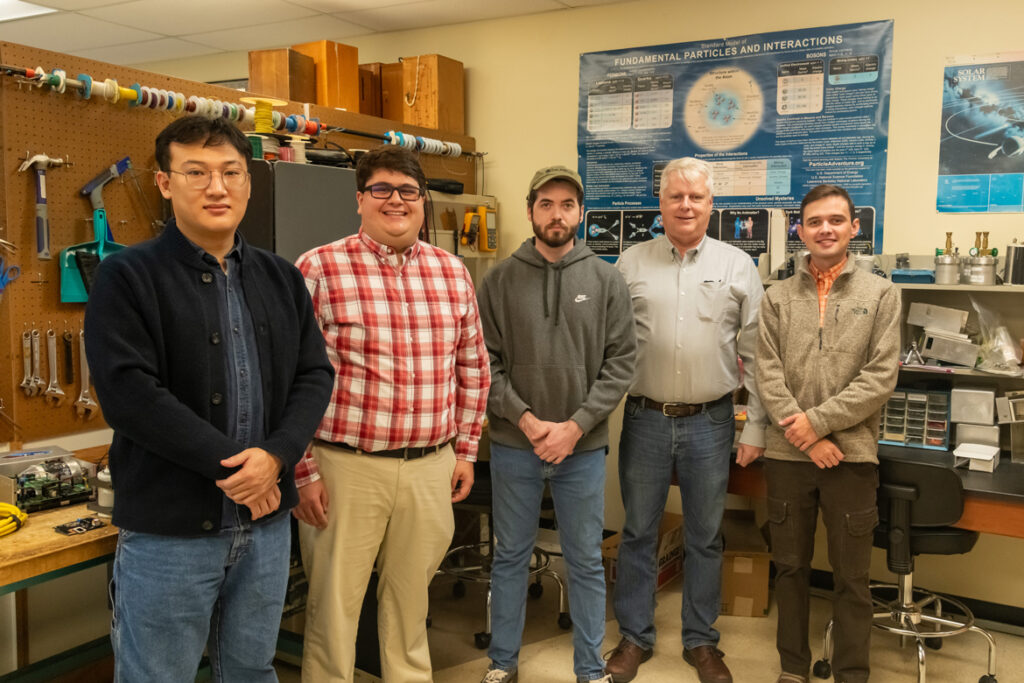

Physics students in Benton’s lab work together in progressing radiation research.

“I’m immensely proud of all these guys. Physics provides great hands-on opportunities for students. It’s not so much about learning something specific, it’s about learning how to learn,” Benton said. “When they come out with an undergraduate degree, they have a sort of physics tool kit that allows them to learn whatever it is they need for whichever career they choose. And that’s what the job is about: helping students and sending them on their way.”