This article, written by Ari Fife, is courtesy of Oklahoma Watch.

TULSA, Okla. (Oklahoma Watch) — The front half of Jasmine Stewart’s north Tulsa living room is traditional. She has clean white sofas and a framed picture of her family, well-lit by skylights.

But for about nine hours each weekday, the back half is taken over by 10 children up to 4 years old. They play on a colorful mat, use a large table for arts and crafts, dig supplies and headphones out of totes lined up on a shelf, and sleep in cribs in her sunroom.

Stewart is among the 1,430 Oklahomans who operated a daycare out of their home in any given month in 2022. These daycares make up the bulk of Tulsa’s 371 licensed childcare businesses.

“(I) just wanted this to be my social work, my wraparound services to offer what I feel like I was called to do,” Stewart said.

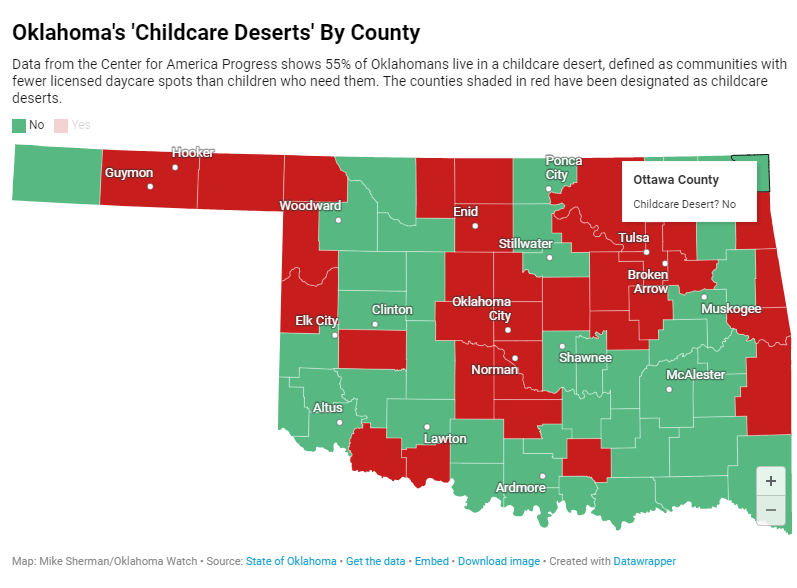

Data shows that providers like Stewart are already scarce, as 55% of the state’s population lives in what has been termed a childcare desert. Zoning codes play a role in that scarcity, regulating where in-home childcare like Stewart’s can and cannot be offered.

To address the problem, a first-term state legislator from Tulsa has authored a bill that would prevent local governments from limiting childcare capacities. Meanwhile, the Tulsa City Council is considering removing some local regulations, including one prohibiting daycares with more than seven children from operating in neighborhoods without a city board exemption.

At issue is whether municipalities can strike a balance that maintains the character of neighborhoods while increasing the availability of affordable, quality childcare close to home.

Efforts to Decrease Regulations in Tulsa

Almost half of Oklahoma’s 77 counties, including Tulsa, are defined as childcare deserts, according to the Center for American Progress, which studies social issues including childcare. Last fall, the state Department of Human Services cited the group’s national study, which applied a childcare desert label to communities with fewer spots in licensed daycares than children who need them.

An Oklahoma Watch analysis of Department of Human Services data shows the majority of Tulsa’s in-home childcare is concentrated in the city’s north and west neighborhoods.

In November, the Tulsa City Council started its reconsideration process. Final recommendations haven’t been made, meaning that Stewart is still preparing to have to appear in front of the city’s Board of Adjustment, which would expect her to prove that her business is in line with “the spirit and intent” of the zoning code and won’t be “injurious to the neighborhood or public welfare.”

Requesting the exemption would also mean paying a $500 fee that equates to about two weeks of tuition for one student, and several hours away from work on a weekday.

The alternative — downsizing to seven kids to avoid the hassle — would mean breaking up friendships and letting go of two assistants who handle most teaching responsibilities and serve meals. For Stewart, who’s always had the goal of growing her facility, it would feel like a return to square one.

Tammy Maus, the president of the Licensed Childcare Association of Oklahoma, said while the restrictions’ impacts on childcare owners might be the most obvious, effects on parents can also be significant. She said many parents aren’t able to work if they don’t have someone to care for their children, and some families prefer the flexible hours and tight-knit environments of in-home childcare.

If Stewart decides to downsize, it would leave Jeryaun Perry and other parents vying for one of three fewer spots. And if Perry is unsuccessful, it would mean a disruption in his family’s routine as they return to the frustrating search for childcare.

Perry, 38, moved from Oklahoma City to Tulsa about five months ago and started searching for childcare for his year-old daughter, Lynnox, before finding Stewart’s facility.

He said he was immediately impressed with her care and flexibility, and her business allows him and his wife to work from home, making it worth the 10-minute commute.

“It was kind of a blessing that we were able to find (Stewart) at the time we were able to find her,” Perry said. “(If the zoning requirements aren’t changed), it’d definitely be an injustice to a lot of families who definitely need the care.”

Conflicting Community Concerns

About 100 community members wearing bright blue shirts in support of childcare providers gathered at Rudisill Regional Library for a town hall last month hosted by Vanessa Hall-Harper, who represents north Tulsa on the city council.

Jackie Evans sat near the front of the room, surrounded by other providers. She’s run a home-based childcare in north Tulsa for about 23 years and said she’s been able to keep her 12 slots full consistently because of her history in her community.

She said she’ll meet any requirements to maintain her enrollment, but other providers might not have those options. They already operate on slim margins and she fears that if they’re faced with too many obstacles, they might be discouraged from childcare completely.

Crystal Pearson, a north Tulsa resident who said she lived across the street from an in-home childcare before it moved a few weeks ago, sat on the edge of the room quietly for the first 20 minutes. But after questions about the origin of the regulations in the zoning code, she spoke up to say that she believes the goal of the city is to make sure businesses are operated safely, not to close down facilities.

“The neighborhood is first — the people that live here,” Pearson said. “And if you’re bringing something into the neighborhood that’s going to be injurious or contradictory, that does not need to take place.”

Pearson and two other neighbors filed a city complaint against the daycare that she lived near in November 2021, prompting a city investigation and ultimately, the city council’s zoning code review. Since the daycare changed ownership 11 years ago, the neighborhood has experienced increased traffic and noise, she said.

Tara Tumey, who lived near the same daycare, said families waiting to pick up their children often block the narrow neighborhood street. As president of her neighborhood’s block club, she said she tried to advocate for older neighbors who might need quick access to emergency services.

Tumey said she believes there’s value in having in-home childcare in her community, adding that she went to two home-based centers as a child and enjoyed them. But she said loosening regulations on the facilities could put young lives at risk.

One Proposed Statewide Solution

Democratic Rep. Suzanne Schreiber’s bill passed through the House on Tuesday but must still make it through the Senate. And if it dies before then, towns that want to streamline their own regulations will have to undergo a process like Tulsa’s.

DHS defines an in-home childcare as one with seven kids or fewer, and a large childcare home as one that has between eight and 12 kids. Its 99-page guide on licensing requirements includes information on caregiver qualifications, but it doesn’t have many of the requirements that appear in some zoning codes, like specific lot size requirements.

Amy Friedlander, a consultant for the nonprofit consulting group Opportunities Exchange, said in-home childcare regulations vary by state, and local restrictions often add a complicated layer. Some states have aimed to streamline their regulations.

A 2019 California law defines running an in-home childcare as a “residential use of property” and bars local governments from requiring in-home childcare owners to get a business license or pay a fee or tax. A 2021 Colorado law requires local governments to zone in-home childcare as residential homes and bans them from implementing rules that don’t apply to other residential properties.

Schreiber said she doesn’t intend to prevent city governments in Oklahoma from creating regulations that limit noise and traffic in neighborhoods. She wants to stop them from acting as DHS, which she said most local governments don’t want to do anyway. In Tulsa, that would mean getting rid of the requirement that larger in-home daycares ask for a special exception, she said.

“DHS knows kids and how to keep kids safe,” said Schreiber, a former Tulsa Public Schools board member. “As a state, we’ve entrusted (the) authority to do that licensing process. That’s where we’ve put that — not on a local zoning board.”

Zoning codes in other Oklahoma towns differ from Tulsa. Yukon and McAlester requirements align with DHS capacity limits. Edmond doesn’t allow daycares with more than eight kids to operate in residential areas, city spokesperson Bill Begley said. He also said the city hasn’t received any complaints from childcare providers about the capacity limits, and it will adjust its requirements based on any laws that pass.

Schreiber said she plans to continue acting as an advocate for in-home childcare providers regardless of the bill’s fate.

“For them to be able to be there for their kids but try to fight a zoning law — I don’t want that for them,” Schreiber said. “I want them to be there and be able to take care of their kids and earn money for it.”

Oklahoma Watch, at oklahomawatch.org, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that covers public-policy issues facing the state.